Matter and antimatter react to gravity in the same way. That’s what scientists discovered in an experiment carried out at CERN’s particle accelerators. With this result, doubts about the differences between the two remain, but other methods must be tried to confirm the finding.

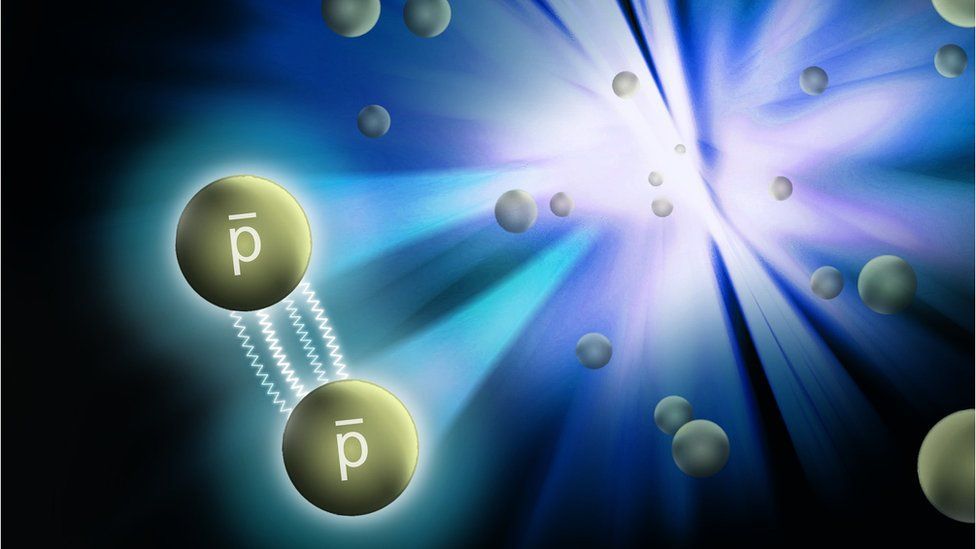

Antimatter is made up of antiparticles—counterparts of the particles we know. For example, while hydrogen is made up of electrons and an atomic nucleus with protons and neutrons, antihydrogen is made up of anti-electrons (or positrons), antiprotons and antineutrons. When they meet, both annihilate each other, leaving only energy behind.

Little else is known about the matter. For example, scientists are still wondering what happened to all the antimatter created at the Big Bang, in the same amount of ordinary matter. Both should have annihilated each other, turning the universe into nothing but energy, but here we are, made of matter, with no objects made of antimatter in the entire observable universe.

Want to catch up on the best tech news of the day? Access and subscribe to our new youtube channel, Kenyannews News. Every day a summary of the main news from the tech world for you!

Matter and antimatter in Earth’s gravity

In current theory, antiparticles do not differ in any way from ordinary particles, except in the electrical charge, which is always opposite. But it wasn’t yet known exactly whether they both respond to gravity in the same way—until now. The experiment was carried out at CERN’s antimatter “factory”.

Over an 18-month period, they confined negatively charged antiprotons and hydrogen ions in something called the Penning trap. In this device, a particle follows a cyclic path with a frequency close to the strength of the magnetic field and the charge-to-mass ratio of the particle.

As the experiment was carried out on Earth, our planet’s gravitational field acted with the same “force” on all particles. Thus, scientists were able to measure the frequencies of the two types of particles. “With this, we were able to obtain the result that they are essentially equivalent, to a degree four times more accurate than the previous measurements”, said Stefan Ulmer, the project leader.

These measurements confirm that the weak equivalence principle established by Albert Einstein is also valid for antimatter. This principle postulates that different bodies in the same gravitational field experience the same acceleration in the absence of frictional forces.

The result is not yet definitive, but Ulmer says these measures could lead to new physics. “The 3% accuracy of the gravitational interaction obtained in this study is comparable to the target accuracy of the gravitational interaction between antimatter and matter that other research groups plan to measure,” he said. “If the results of our study are different from others, it could lead to the emergence of a completely new physics.”

The study was published in the journal Nature.