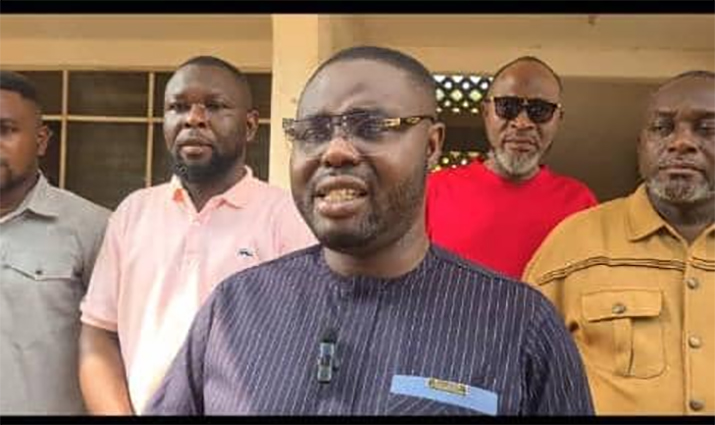

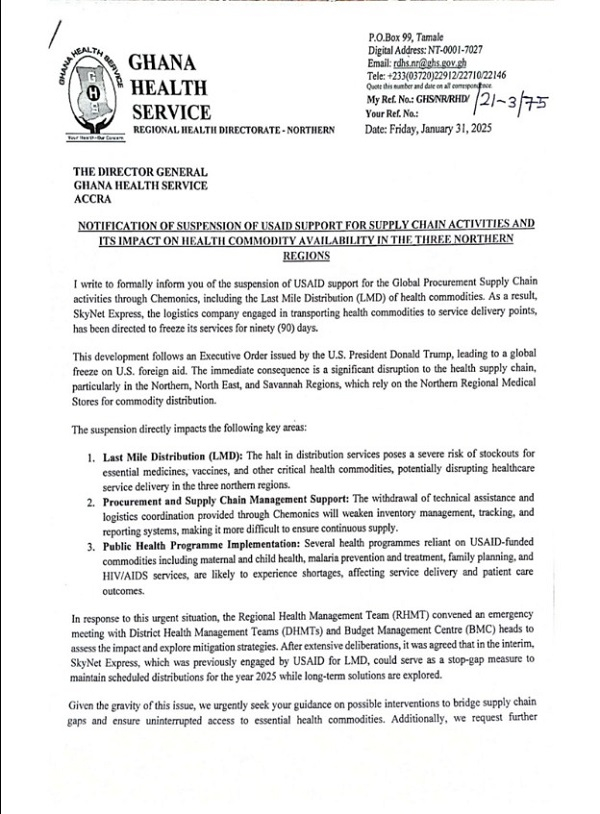

The recent disorder in Ghana’s parliament—where legislators turned to yelling, shoving, and furniture destruction— is more than just an expression of political differences.

Beneath the surface of these intense conflicts is a major emotional control problem that is little talked about but is absolutely vital for good leadership.

Examining the tape or reading the reports, one wonders how a room full of seasoned political leaders with legislative mandate end up in physical altercations like disgruntled students dissatisfied with cafeteria meals? The response is fundamentally psychological.

The Lack of Emotional Control in Leadership

A key quality of a good leader, whether in politics, religion, education, business, or at home, is the skill to handle feelings well. This means managing stress, resolving arguments calmly, and staying calm in tough situations. In Ghana’s parliament, we saw the opposite of emotional control at the top level of government.

To look at this from a psychology angle, let us think about Gross’ Emotion Regulation Theory. James Gross, a leading researcher in emotion regulations, notes that two main approaches can help people control their emotions:

response-oriented regulation—where emotions are controlled after they have already been triggered—and antecedent-focused regulation—where people control their emotional response before it escalates. Effective leaders employ antecedent-focused tactics, such as reappraisal, which involves reframing a situation to diminish its emotional intensity.

The events in parliament indicate that numerous politicians employed maladaptive response-focused methods, including suppression (repressing emotions until they erupt) or overt aggressiveness (attacking physically, vocally, or verbally).

Rather than employing cognitive reappraisal—perceiving the extended vetting process as an essential democratic procedure—certain legislators responded with impulsivity, transforming a political disagreement into a public, or somewhat internationally disgraceful, spectacle.

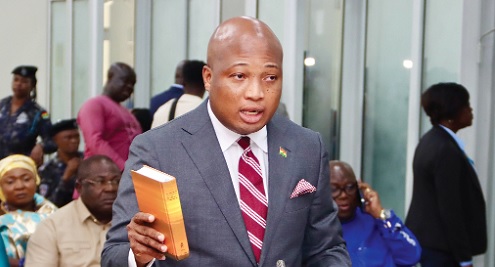

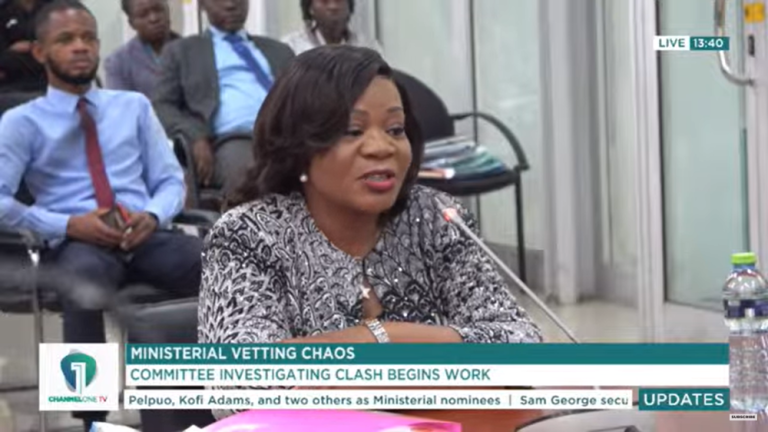

They believed that the opposing members of the vetting committee were retaliating against the vetted minister for criticisms directed at the former president.

Why This Is Important: The Social and Ethical Repercussions

Let us take a moment to consider what this means outside of parliament. Political leaders who act in this manner give the public the unmistakable impression that physical altercations, hostility, and emotional outbursts are acceptable ways to deal with anger.

For young people looking to these leaders as role models, this is especially harmful. Social learning theory, created by Albert Bandura, reminds us that people—especially young adults and children—learn actions by seeing and copying others.

What message does that transmit to society if individuals in positions of authority react to dispute with aggression instead of mutual dialogue? It validates emotional dysregulation and creates a standard that might find its way into homes, businesses, and classrooms. The very persons who should be setting a moral and ethical example are rather encouraging turmoil and antagonism in the public space.

This is why the apologies from the chairman of the vetting committee and the Speaker’s act of suspending the four legislators should be seen as more than just political damage control; it should be a sharp wake-up call. Beyond the required political fallout, a meaningful discussion about mental health and leadership is desperately needed.

The Mental Health Crisis in Leadership

Constant public scrutiny, the weight of national responsibility, and the never-ending cycle of battle in politics can cause great psychological strain on individuals, even the best of us. The great pressure to perform causes leaders to experience persistent stress, worry, and, occasionally, depressed symptoms.

But in many African nations, like Ghana, mental health still is a taboo topic, especially for people in positions of authority. Seeing a professional to address mental health needs is usually seen as weakness rather than competence, intelligence, and self-awareness.

Ironically, there is little to no institutional support for the mental health of persons in positions of authority, despite the fact that leadership demands high levels of emotional intelligence, resilience, and psychological well-being.

These parliamentarians are left to handle high political tensions without the means to properly control their emotions since they lack access to professional psychological resources. Unchecked stress over time can cause burnout, anxiety disorders, even post-traumatic stress—especially in settings where political animosity is prevalent.

The events that transpired in Parliament extend beyond the mere political considerations associated with the scrutiny of ministers. This phenomenon signifies a more critical concern: the oversight of mental health within leadership.

Legislators might have handled the matter differently if they received psychological training on cognitive restructuring, emotional intelligence, and stress management. Instead of turning to violence, they may have resolved teething issues through active listening, de-escalation techniques, and negotiating abilities.

The Call for Psychological Support for Governance

The necessity for organized mental health support for political leaders has become increasingly evident. The following are several fundamental steps:

1. Emotional Intelligence Training – It is imperative that leaders participate in ongoing training focused on the management of emotions, effective communication, and the ability to maintain composure in high-pressure situations. This ought to be an institutional need rather than a side issue.

2. Mental Health Professional Access: Government officials should have organized psychological help akin to what companies provide for top executives—executive coaching and counseling including resiliency training.

3. Leaders need instruction on coping mechanisms for worry, stress, and emotional tiredness to meet the demands of government. Leadership development should incorporate preventative elements such cognitive behavioral techniques and mindfulness to enhance the personal well-being of parliamentarians.

4. Education in Ethical Leadership: Ethical governance has to take the center stage of leadership development for parliamentarians. Political leaders should realize that self-regulation is a necessary component of good leadership since their actions define public behavior.

Time to Change Our Viewpoint

The turmoil in Ghana’s parliament should be regarded as a mental health and ethical problem rather than merely political drama to discount. Effective leadership is based on the ability to control one’s emotions, although we frequently witness political leaders struggling with this.

For politicians, for systems of government, and for society at large, this is a wake-up call. It is time to start tackling the underlying issue instead of merely apologizing and suspending offenders. Political leaders have to be armed with psychological instruments to control emotions, negotiate stress, and practice moral leadership.

Any democracy runs a great risk if we keep neglecting the mental health needs of those in power since it will lead to a leadership culture that favors political successes over personal integrity and psychological well-being.