“It’s personally embarrassing for myself to have to explain to friends and family members why I’m getting fired,” says one former Meta employee, who was fired as part of the company’s layoffs in late 2022 and requested anonymity to avoid jeopardizing her future job prospects.

But it isn’t just the suddenness, but also the dehumanizing way that the announcements were made, which rankles staff who have been let go. When it finally came, the email telling Bowling he was being laid off from Google was “legalese,” and was signed off by the company’s vice president without any salutation.

“No sincerely, no sorry, nothing,” he says. “It was written by a lawyer, so there was no implied guilt or anything in there. It was so cold. Everything about it was so cold.”

The company has historically treated employees fairly well, even when they exit, according to Bowling. “This layoff was so different from the culture of how people leave the company,” he says.

Google did not respond to a request for comment.

But for Susan Schurman, a professor of labor studies and employment relations at Rutgers University, the gap between how tech companies portray themselves and how they act was always there.

“It would be fair to say I’m shocked but not surprised,” Schurman says. “I’m old enough to have been brought up in a so-called 20th-century organization, where you could say workers are viewed as expendable commodities.”

Attitudes toward staff have also worsened during the pandemic, according to Cary Cooper, professor of organizational psychology at the University of Manchester Business School. Remote working created a greater separation between managers and their employees. “There was less face-to-face contact, and much more of their communications were virtual,” he says. “That could create a situation where you don’t develop a close relationship with your employees, if you’re a line manager.”

Some tech workers say that they’d already come to realize that tech companies won’t necessarily return their loyalty.

“Honestly, a couple of years ago, I started changing my mindset about the companies I work for,” says Alejandra Hernandez, a recruiting program manager at Meta, who was laid off in November after working for the company for a year. “I’m looking at it as: ‘This is a business, you hired me to do certain work.’” Hernandez points out that being employed in California means she’s employed at will, and can be terminated at any time—which helped recalibrate her thinking.

Hernandez wasn’t too upset about the way that she and her colleagues were laid off by email. “I would much rather be emailed than have someone try to butter me up on a Zoom call about letting me go,” she said.

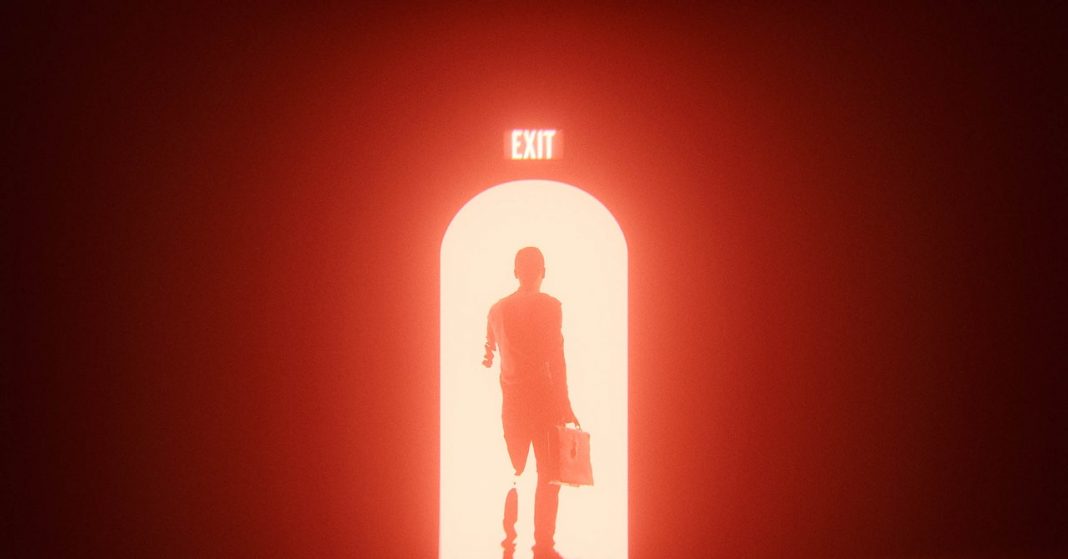

Even for those who have survived the layoffs, the past few months have acted as a sharp reminder that their well-being will never come before executives’ fiduciary duties, and that when times get tough their positions are vulnerable.

“We were all deluded into thinking these tech companies were treating people as human beings,” says Schurman. “But I think we’ve found out that it was only possible at the time, and as soon as times get tough—boom: The boss is back.”