Lilhari believes that his endorsed, stealth political videos can be a significant factor in the upcoming elections. A majority of his Instagram’s reach is among the 16-24 age group. “My viewers will remember the name of the candidate I spent my day with—and it will stay in the memories of the first-time voters, who are young and not very knowledgeable.”

Influencers aren’t only useful for promotion—they can help candidates head off bad press. In late October, Deepti Maheswari, the 36-year-old BJP candidate from Rajsamand, in Rajasthan (who is an influencer in her own right), was caught up in a controversy after party workers stormed into her office to protest her selection for the ticket. Maheshwari is from the nearby city of Udaipur; party workers wanted a local candidate. But Bharat Chouhan, Maheswari’s 31-year-old social media manager, says he was able to head off the crisis by preparing “an army of nearly 1,000 nano-influencers to dilute the narrative against the BJP on social media.”

“The protest videos were all over social media, but my team went to every post and spammed it with ‘Ayegi toh BJP hi!’ [Only BJP will win the election],” he says. WIRED verified that this and similar statements appear under many posts about the protests.

While these political collaborations can be lucrative, they are a delicate balancing act for influencers. An overt endorsement can lead to an online backlash from followers. Hamraj Singh, who managed the BJP’s campaigns in the northern state of Himachal Pradesh in November 2022, told WIRED that at least two influencers had taken down posts following the backlash. “We convinced an Instagram handle with 50,000 followers to post our content,” he says, “but it fell on our face and was removed by the influencer.”

“The politicians, like access to the prime minister’s office, bring higher credibility to the influencers,” says Ranade, the VP at Dentsu India. “If done well, the subliminal use of influencers can be done very economically and effectively. But they are also ‘canceled’ for having a steep political opinion,” she says. “It is a delicate deal for influencers. It is an offer they cannot refuse, but it comes with a cost.”

These deals can also be a legal tightrope for influencers to walk. Beginning in August this year, the Advertising Standards Council of India demands that influencers disclose if a post was an endorsement or an advertisement. None of the influencers interviewed by WIRED included any such disclosure.

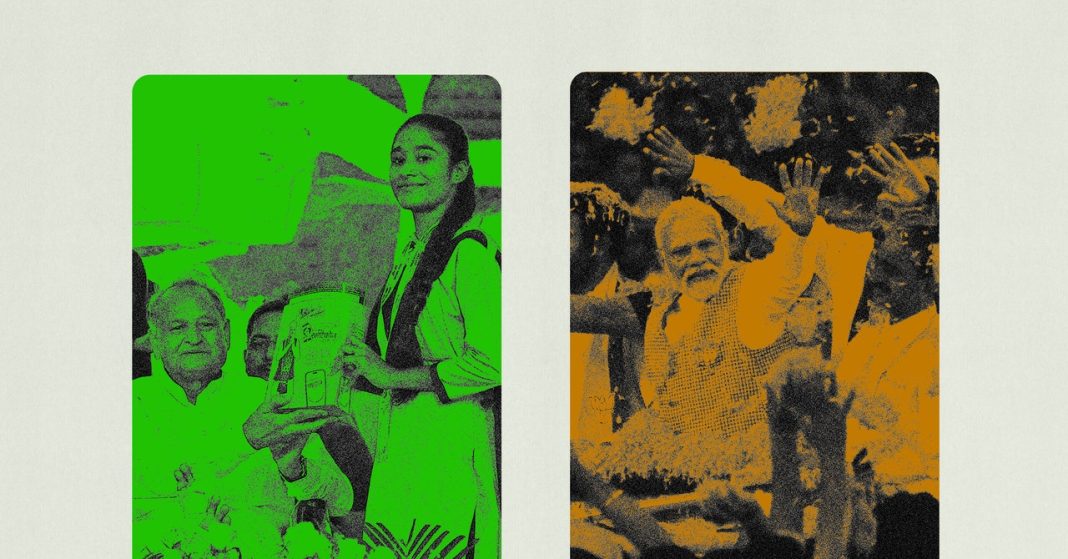

The next year’s national election is largely seen as a contest for “the idea of India” as a country, which has steadily fallen in indices of democratic freedom under Modi’s Hindu-nationalist regime. Modi’s party rode to power in 2014 by weaponizing social media platforms. The 2024 elections are likely to be a continuation of that, with widespread misinformation and hate speech that may threaten the integrity of the democratic process. The influencer space is a new battleground—one which needs careful oversight.

But, says Pal, the associate professor, the people most able to deal with the problem are the ones who profit the most from it. “It is also not in the interest of the ruling government [to address the concerns], because they are better mobilized in this ecosystem,” he says. “It is a very dangerous situation, and we are unfortunately destined to see a lot of this happening in upcoming elections.”