Interoperability and decentralization have been major themes in tech this year, driven in large part by mounting regulation, societal and industrial pressure and the hype trains that are crypto and web3. That rising tide is lifting other boats, such as an open standards-based communication protocol called Matrix — which is playing a part in bringing interoperability to another proprietary part of our digital lives: messaging.

The number of people on the Matrix network doubled in size this year, according to Matthew Hodgson, one of Matrix’s co-creators — a notable, if modest, boost to 80.3 million users (that number may be higher; not all Matrix deployments “phone home” stats to Matrix.org).

While the bulk of all this activity has been in enterprise communications, it looks like mainstream consumer platforms might now also be taking notice.

Some sleuthing from engineer and app researcher Jane Manchun Wong unearthed evidence that Reddit is experimenting with Matrix for its chat feature — a move more or less confirmed to by Reddit. A spokesperson said that it’s “looking at a number ways to improve conversations on Reddit” and was “testing a number of options,” though they stopped short of name-checking Matrix specifically.

Given the bigger swing in support of interoperability — it’s happening also in digital wallets and maps — a closer look at Matrix gives some insight into how we got here.

In the beginning

View from above hands holding mobile phones. Image Credits: Malte Mueller / Getty

Anyone who has ever sent an SMS or email won’t have considered for a second what network, service provider or messaging client their intended recipient used. The main reason is that it doesn’t really matter — T-Mobile and Verizon customers can text each other just fine, while Gmail and Outlook users have no problems emailing each other.

But that wasn’t always the case. In the earliest days of electronic mail, you could only message users on the same network. As mobile phones proliferated throughout the 1990s, people initially couldn’t message their friends if they were on a different mobile network. Europe and Asia led the charge on interoperability, and by the start of the millennium the big North American telcos also realized they could unlock a veritable goldmine if they allowed consumers to message their friends on rival networks. It was a win-win for everyone.

Fast-forward to the modern smartphone age, and while email hasn’t exactly gone the way of the dodo and SMS is still stuttering along, the preeminent communication tools of today aren’t nearly as friendly with each other. Those looking to embrace independent privacy-focused messaging apps such as Signal will hit a brick wall when they realize that literally all their pals are using WhatsApp. Or iMessage. Or Telegram. Or Viber … you get the picture.

This trend permeates the enterprise realm, too. If your work uses Slack, good luck sending a message to your buddy across town forced to use Microsoft Teams, while those in human resources shoehorned onto Meta’s Workplace can think again about DM-ing their sales’ colleagues along the corridor using Salesforce Chatter.

This is nothing new, of course, but the issue of interoperability in the online messaging sphere has come sharply into focus in 2022. Europe is pushing ahead with rules to force interoperability and portability between online platforms via the Digital Markets Act (DMA), while the U.S. has similar plans via the ACCESS Act.

Meanwhile, Elon Musk’s arrival at Twitter has driven awareness of alternatives such as Mastodon, the so-called “open source Twitter alternative” that shot past 2 million users off the back of the chaos at Twitter. Mastodon is powered by the open ActivityPub protocol and is built around the concept of the fediverse: a decentralized network of interconnected servers that allow different ActivityPub-powered services to communicate with each other. Tumblr recently revealed that it intends to support the ActivityPub protocol in the future, while Flickr CEO Don MacAskill polled his Twitter followers on whether the photo-hosting platform and community should also adopt ActivityPub.

But despite all the hullaballoo and hype around interoperability spurred by the Twitter circus in recent weeks, there was already a quiet-but-growing movement in this direction; a movement driven by enterprises and governments seeking to avoid vendor lock-in and garner greater control of their data stack.

Enter the Matrix

Element founders and Matrix co-creators Matthew Hodgson and Amandine Le Pape. Image Credits: Element

Matrix was developed inside software and services company Amdocs back in 2014, spearheaded by Hodgson and Amandine Le Pape who later left the company to focus entirely on growing Matrix as an independent open source project. They also sought to commercialize Matrix through a company called New Vector, which developed a Matrix hosting service and a Slack alternative app called Riot. In 2018, Hodgson and Le Pape launched the Matrix.org Foundation to serve as a legal entity and guardian for all-things Matrix, including protecting its intellectual property, managing donations and pushing the protocol forward.

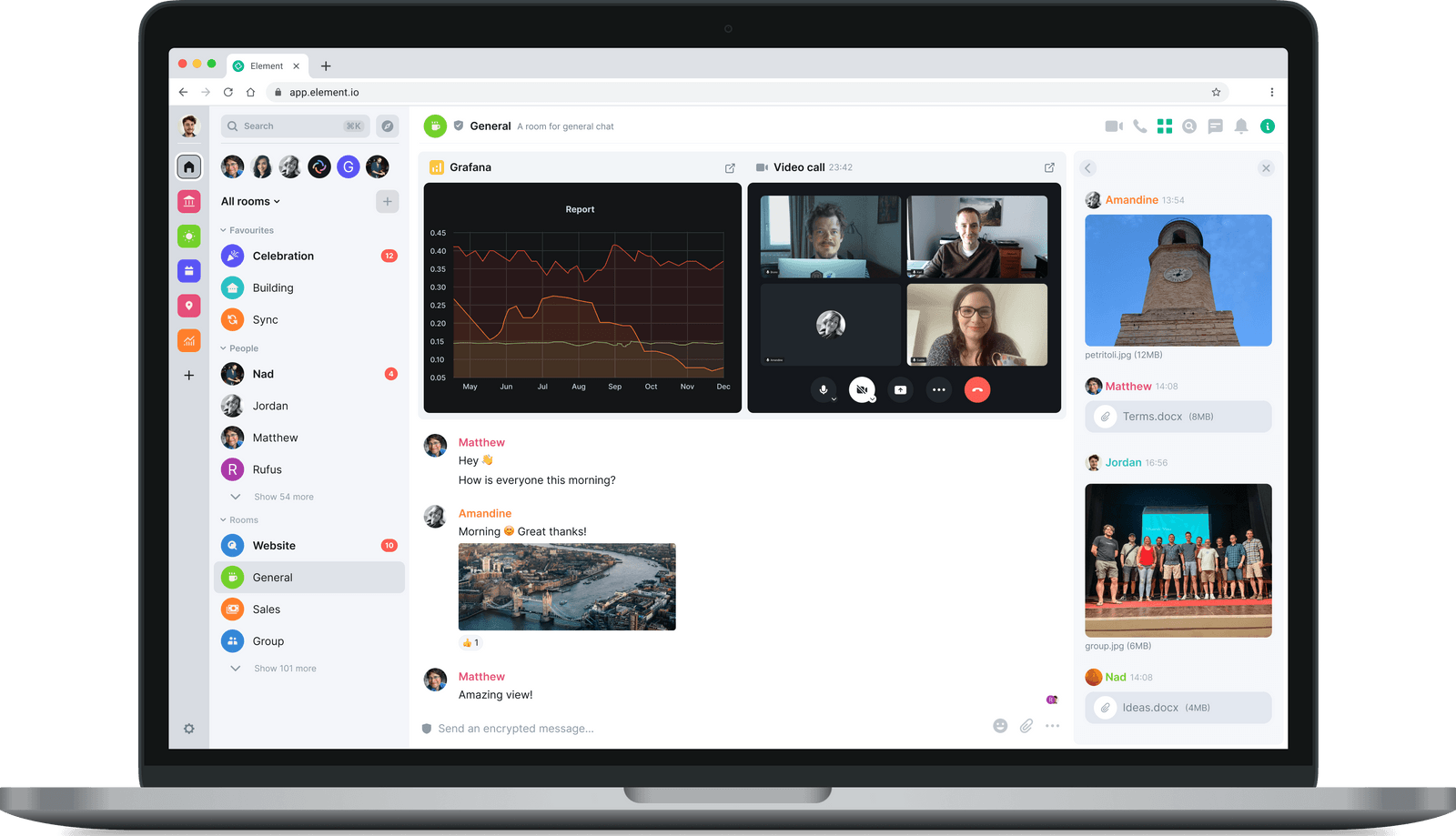

The flagship commercial implementation of Matrix was rebranded as Element a little more than two years ago, and today Element — backed by Automattic, Dawn Capital, Notion, Protocol Labs and others — is used by a host of organizations looking for a federated alternative to the big-name incumbents sold by U.S. tech giants.

Element itself is open source and promises end-to-end encryption, while its customers can access the usual cross-platform features most would expect from a team collaboration product, including group messaging and voice and video chat.

Element in action. Image Credits: Element

Element can also be hosted on companies’ own infrastructure, circumventing concerns about how their data may be (mis)used on third-party servers, ensuring they remain in control of their full data stack — a deal-maker or breaker for entities that host sensitive data.

A growing array of regulations, particularly in Europe, are forcing Big Tech to pay attention to data sovereignty, with the likes of Google partnering with Deutsche Telekom’s IT services and consulting subsidiary T-Systems last year to offer German companies a “sovereign cloud” for their sensitive data.

This regulatory push, alongside growing expectations around data sovereignty, has been a boon for the Matrix protocol. Last year, the agency responsible for digitalizing Germany’s health care system revealed that it was transitioning to Matrix, ensuring that the 150,000 individual entities that constitute the health care industry such as hospitals, clinics and insurance companies, could communicate with each other regardless of what Matrix-based app they used.

This builds on existing Matrix implementations elsewhere, including inside the French government via the Tchap team collaboration platform, as well as the German armed forces Bundeswehr.

“The pendulum has been clearly swinging toward decentralization for quite a while,” Hodgson explained to . “We’re now seeing serious use of Matrix-based decentralized communications across or within the French, German, U.K, Swedish, Finnish and U.S governments, as well as the likes of NATO and adjacent organizations.”

Back in May, open source enterprise messaging platform Rocket.Chat revealed that it would be transitioning to the Matrix protocol. While this process is still ongoing, this represented a major coup for the Matrix movement, given that Rocket.Chat claims some 12 million users across major organizations such as Audi, Continental and Germany’s national railway company, The Deutsche Bahn.

“We believe that the value of any messaging platform grows based on its ability to connect with other platforms,” a Rocket.Chat spokesperson told . “We put a lot of effort into connecting Rocket.Chat with other platforms. We don’t have to worry about what client we use when emailing each other, and the same should be true when we’re messaging each other.”

Rocket.Chat. Image Credits: Rocket.Chat

What’s perhaps most interesting about all this is that it runs contrary to the path that traditional consumer and enterprise social networks, and team collaboration tools, have taken.

Slack, Facebook, Microsoft Teams, WhatsApp, Twitter and all the rest are all about harnessing the network effect, where a product’s value is intrinsically linked to the number of users on it. People, ultimately, want to be where their friends and work colleagues are, which inevitably means sticking with a social network they don’t particularly like or using multiple different apps simultaneously.

Open and interoperable protocols support a new breed of business that’s cognizant of the growing demand for something that doesn’t lock users in.

“Our goal is not to force people to use Rocket.Chat in order to communicate with each other,” Rocket.Chat’s spokesperson continued. “Rather, our goal is to enable organizations to collaborate securely and connect with other organizations and individuals across the platforms of their choosing.”

Bridging the divide

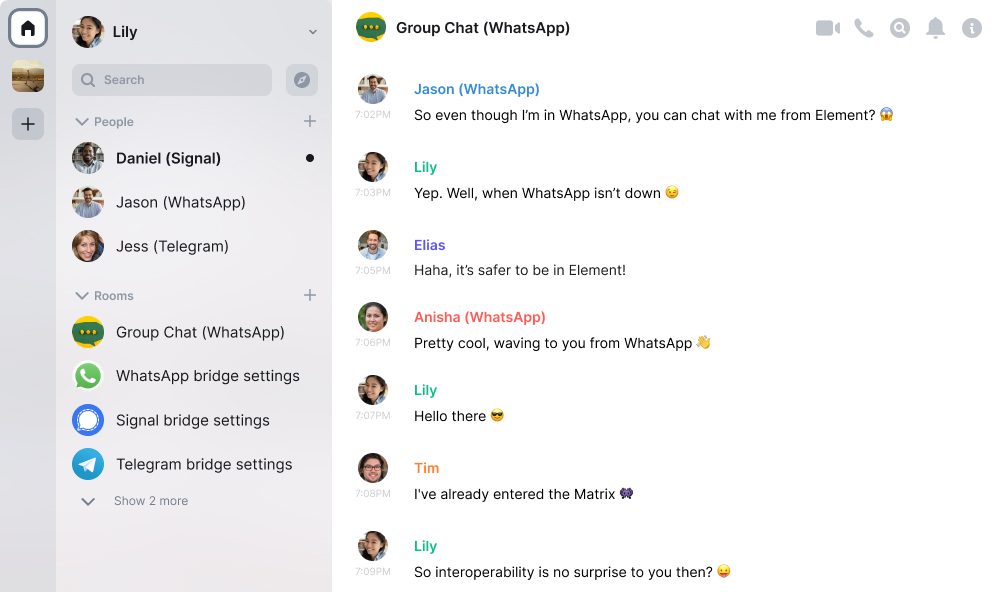

The Matrix protocol also supports non-native interoperability through a technique called “bridging,” which ushers in support for non-Matrix apps, including WhatsApp, Telegram and Signal. Element itself offers bridging as part of a consumer-focused subscription product called Element One, where users pay $5 per month to bring all their friends together into a single interface — irrespective of what app they use.

Element One subscribers can bring different messaging apps together. Image Credits: The Matrix Foundation

This is enabled through publicly available APIs created by the tech companies themselves. However, terms of use are typically restrictive with regard to how they can be used by competing apps, while they may also enforce rate limits or usage costs.

Bridging as it stands sits somewhere in a grey area from a “is this allowed?” perspective. But with the world’s regulatory eyes laser focused on Big Tech’s stranglehold on online communications, the companies perhaps don’t enforce all their T&Cs too rigorously.

The DMA came into force in Europe last month — though it won’t officially become applicable until next May — and it has specific provisions for interoperability and data portability. At that point, we’ll perhaps start to see how the Big Tech “gatekeepers” of the world plan to support the new regulations. In reality, what we’re talking about are open APIs that “formally” permit smaller third parties to integrate and communicate with their Big Tech brethren. This doesn’t necessarily mean that such APIs will be slick and easy-to-use with clear documentation though, and we can probably expect some deliberate heel-dragging and hurdles along the way.

Compliance

WhatsApp and Facebook application displayed on a iPhone. Image Credits: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Popular messaging apps such as WhatsApp, while offering end-to-end encryption, weren’t designed for enterprise or governmental use cases as they don’t allow organizations to easily manage any of their messaging data — yet such apps are widely used in such scenarios. Back in July, the U.K.’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) called for a government review into the risks around “private correspondence channels” such as personal email accounts and WhatsApp, noting that such usage lacked “clear controls” and could lead to the loss of key information being “lost or insecurely handled.”

“I understand the value of instant communication that something like WhatsApp can bring, particularly during the pandemic where officials were forced to make quick decisions and work to meet varying demands,” U.K. information commissioner John Edwards said in a statement at the time. “However, the price of using these methods, although not against the law, must not result in a lack of transparency and inadequate data security. Public officials should be able to show their workings, for both record keeping purposes and to maintain public confidence. That is how trust in those decisions is secured and lessons are learnt for the future.”

In the business realm, meanwhile, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) recently settled with 16 Wall Street firms for $1.1 billion over “widespread recordkeeping failures” related to their use of private messaging apps such as WhatsApp.

“Finance, ultimately, depends on trust,” SEC Chair Gary Gensler said at the time. “Since the 1930s, such record keeping has been vital to preserve market integrity. As technology changes, it’s even more important that registrants appropriately conduct their communications about business matters within only official channels, and they must maintain and preserve those communications.”

Maintaining an accurate paper trail, and ensuring that politicians and businesses are accountable for their actions, is the name of the game — a level of control that something like the Matrix protocol promises. However, mandating that every company over a certain size — as the DMA regulation does — has to make their software interoperable with others raises a bunch of questions around privacy, security and the broader user experience.

The encryption elephant in the room

Concept illustration of “elephant in the room.” Image Credits: Klyaksun/Getty Images

As Casey Newton has noted over at The Platformer on more than one occasion, Europe’s new interoperability regulations come with several pitfalls. Chief among them, perhaps, being the hurdles they will create for end-to-end encryption — that is, ensuring that data remains encrypted and impossible to decode while in transit.

End-to-end encryption is a huge selling point for the big technology companies of today, one that WhatsApp hollers from the rooftops. But making this work between different platforms built by different companies is not exactly easy, and many — if not most — experts on the subject say that it’s not possible to enforce a truly secure, interoperable messaging infrastructure that doesn’t compromise encryption in some way.

WhatsApp can control — and therefore promise — end-to-end encryption on its own platform. But if billions of messages are flying between WhatsApp and countless other applications run by other companies, WhatsApp can’t really know what’s happening to these messages once they leave WhatsApp.

Ultimately, no two services deploy their encryption identically, a challenge that Hodgson acknowledges. “End-to-end encrypted platforms have to speak the same language from end to end,” he said.

In a blog post published earlier this year to address encryption concerns, the Matrix Foundation suggested some workarounds, including having all the big gatekeepers switch to the same “decentralized end-to-end protocol” (i.e., Matrix, unsurprisingly) which, by the Foundation’s own admission, would be a large undertaking — but one “we shouldn’t rule out,” it said.

To illustrate this point, Hodgson pointed to Element’s 2020 acquisition of Gitter, a developer-focused community and chat platform purchased from GitLab and used by big-name companies including Google, Microsoft and Amazon. Within two months of closing the deal, Element had introduced native Matrix connectivity to Gitter.

Coordinating such a transition on a Facebook, Google or Apple scale would be an entirely different proposition, of course; one that could cause all manner of knock-on chaos. In a blog post earlier this year, cryptography and security expert Alec Muffett suggested that messaging apps and social networks adhering to the same standard protocol would lead to “no practical differentiation” between different services.

“Imagine a world where Signal and Snapchat would have to interoperate — what would that look like?” Muffett asked rhetorically in a Q&A for this story. “Specifically, which features from one needs to be presented on the other, and what are the differentiators surrounding those features? And how would conflict in functionality be reconciled?”

This is why the Matrix Foundation proposed other potential solutions, such as adopting a TLS certificate-style warning, where the user is alerted to the fact that their cross-service conversation is not fully protected. This is perhaps comparable to how Apple’s Messages app supports both encrypted iMessage texts and (unencrypted) SMS. But according to Muffett, it would bring unnecessary complexity to the mix.

“Apart from any other reason that I could cite, there is any amount of user interface research which explains that security-pop-up-warnings are generally not understood and not heeded,” Muffett said. “There is tons of research to back this up — popup warnings are an ‘anti-pattern.’”

The Matrix Foundation also proposed converting communication traffic between encryption languages in a “bridge,” though this would effectively mean having to break the encryption and re-encrypt the traffic safely somewhere.

“These bridges could be run client-side — for example, the Matrix iMessage bridge runs client-side on iPhone or Mac — or by using client-side open APIs to bridge between the apps locally within the phone itself,” Hodgson said. “Alternatively, they could be run server-side on hardware controlled by the user in a decentralized fashion, ensuring that the re-encryption happens in as secure an environment as possible, rather than on a vulnerable centralized server.”

There’s no escaping the fact that breaking encryption is far from ideal, irrespective of how a solution proposes to reconcile this. But perhaps more importantly, a robust solution for addressing the real encryption issues introduced by enforced interoperability doesn’t truly exist yet.

Despite that, Hodgson has said in the past that the upsides of the new EU regulations are greater than the downsides.

“On balance, we think that the benefits of mandating open APIs outweigh the risks that someone is going to run a vulnerable large-scale bridge and undermine everyone’s E2EE,” he wrote in May. “It’s better to have the option to be able to get at your data in the first place than be held hostage in a walled garden.”

Tip of the iceberg

It’s worth noting that the Matrix protocol, while chiefly known for its presence in the messaging realm today, has other potential applications too. The Matrix Foundation recently announced Third Room, a decentralized and interoperable metaverse platform built on Matrix. This runs contrary to a potential future metaverse controlled by a handful of gatekeepers such as Facebook’s parent company Meta.

For now, Element remains the flagship poster child of what a Matrix-powered world could look like. The company has secured some big-name customers already, such as Mozilla, which is using Element as a fully managed service, while Element said that it signed an $18 million four-year deal with another (unnamed) company this year. Meanwhile, it also has strategic backers, among them WordPress.com parent Automattic, which first invested $4.6 million in Element back in 2020 before returning for its $30 million Series B last year.

In many ways, the ground has never been so fertile for Matrix to flourish: it’s in the right place at the right time, as the world seeks an exit route from Big Tech’s clutches backed by at least a little regulation. Twitter, too, has played more than a bit part in highlighting the downsides of centralized control, playing into the hands of all the companies banging the interoperability drum.

“The situation at Twitter has been absolutely amazing in terms of building awareness of the perils of centralization, providing a pivotal moment in helping users discover that we are entering a golden age of decentralization,” Hodgson said. “Just as many users have discovered that Mastodon is an increasingly viable decentralized alternative to Twitter, we’ve seen a massive halo effect of users discovering Matrix as a way to reclaim their independence over real-time communications such as messaging and VoIP — our long-term user base in particular is growing at its fastest-ever rate.”