His hedge fund investors didn’t want to listen to him when, in 1999, Julian Robertson questioned the sanity of the prices being paid for shares in nascent internet companies. So months after being berated for 15 minutes at an annual shareholders meeting at the Plaza Hotel in New York in October 1999, he began the process of closing up his shop. “There is no point in subjecting our investors to risk in a market which I frankly do not understand,” he reportedly wrote to them in March of 2000. “After thorough consideration, I have decided to return all capital to our investors, effectively bringing down the curtain on the Tiger funds.”

In April 2000, the tech market began to implode.

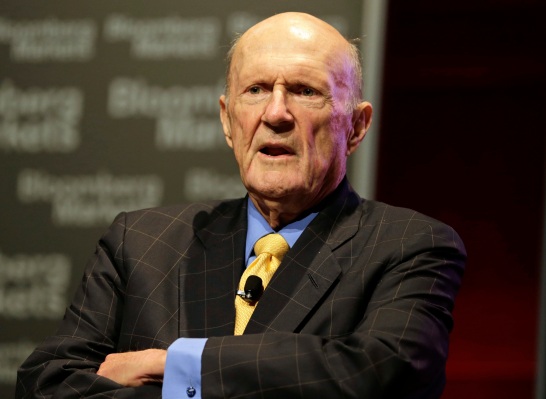

His good timing only cemented the legend of Robertson, who just passed away at age 90 of cardiac complications, according to his spokesman, but who, until he was 67, led Tiger Management, one of the largest, highest-profile, and best-performing funds in the 70-year-old hedge fund industry.

One needn’t look far to appreciate his lasting impact. While Tiger Management reportedly boasted average annual gains of more than 30% for the 20 years it was up and running, the wide spate of investment managers who cut their teeth as part of Robertson’s 200-person team has become nearly as legendary. Among the many hedge funds run by people who worked with Robertson — they’re famously known as “Tiger Cubs” — are Tiger Global, Lone Pine, Coatue Management, Viking Global, D1 Capital and Pantera Capital, and that’s just a sampling.

“In a weird way, Julian Robertson touches trillions of dollars of assets under management because there are so many people who worked for him directly [or] indirectly,” Daniel Strachman, author of Julian Robertson: A Tiger in the Land of Bulls and Bears, told the Financial Times last year.

Unsurprisingly, Robertson’s mentees speak glowingly of him, as an investor, as well as a philanthropist. In addition to Robertson’s own family foundation, and Tiger Foundation, a nonprofit that says it has provided more than $250 million in grants to organizations working to break the cycle of poverty in New York City, Robertson in 2017 signed the Giving Pledge, which asks participants to give at least half of their wealth away.

One of those protégés is Coatue founder Philippe Laffont, who spent three years working for Robertson before striking out on his own in 1999 with a reported $45 million that, unlike Robertson, he promptly began plowing into tech shares. (Laffont lost money on the downturn the following year, but navigated his way through it.)

Coatue — a crossover fund named after a beach off the coast of Nantucket — has gotten squeezed again this year by the downturn in both public and private tech stocks. Still, Coatue had grown its assets under management to nearly $60 billion by the end of last year, and Laffont seemingly credits Robertson for some of that success.

“Julian was a legendary investor and a generous mentor,” said Laffont in a statement sent to this morning. “He did so much good in the world, and so often when nobody was looking,” wrote Laffont. “We all feel lonelier without him here. He leaves a beautiful legacy that so many of us will continue to seek to live up to. I consider myself fortunate to have had his friendship and mentorship in my life.”

Another of Robertson’s famous mentees is Chase Coleman, who worked as an investment analyst at Tiger Management for nearly four years before the hedge fund wound down. Coleman, who launched Tiger Global Management the following year, in 2001, also credits Robertson for much of the career he has enjoyed.

In a statement sent to earlier today, Coleman writes: “Julian was a pioneer and a giant in our industry, respected as much for his abilities as an investor as for the integrity, honesty, loyalty and competitiveness he demonstrated as a leader. He made the time to be a true mentor, always leading by example and pushing all of us to become the best versions of ourselves. For that and for his friendship, I am forever grateful. He will be dearly missed, but his impact on me and countless others, as well as the many communities he touched through his philanthropic efforts, will endure.”

Like Coatue, Tiger Global is a crossover fund that has increasingly invested in private tech companies as well as publicly traded ones. Like Coatue, it has also had a comparatively tough 2022, owing to the market’s breathtaking zigs and zags. (In fairness, the same is true of many outfits, including Viking Global, whose founder, Andreas Halvorsen, once traded equities at Tiger Management and, like Laffont, struck out on his own, with Viking, in 1999. His flagship fund is on track for its worst year ever, Bloomberg reported last month.)

Indeed, it’s easy to wonder what Robertson — whose success tied to buying underpriced stocks with good earnings prospects — thought of these cubs’ aggressive moves into late-stage privately held tech companies, particularly given that some of them were paying any price last year, and driving valuations sky high in the process.

If Robertson did ever question their various approaches, he never said so publicly. Even when Archegos Capital Management — the family office of another protégé, Bill Hwang — suddenly collapsed in spectacular fashion last year (Hwang was charged with massive fraud by the SEC in April), Robertson came to Hwang’s defense in a rare interview with the FT, telling the outlet last summer: “Bill is a good friend, and I know Bill well. I think he made a mistake and I expect that he’s coming out of it and he’ll go right on.”