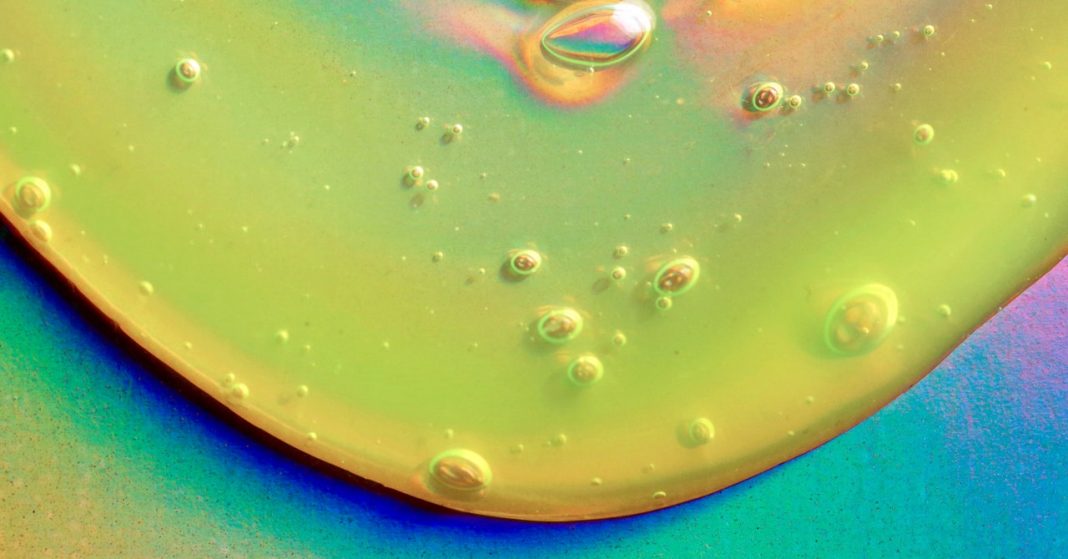

Katharina Ribbeck’s lab collects mucus—the often gooey substance present in places like the mouth, gut, reproductive tract, and intestines. While the slimy goop may not be pretty from the get-go, a purification process can brighten it up. “Once you remove particulates and microbes, it’s a beautiful, beautiful clear gel—like egg white,” says Ribbeck, a professor of bioengineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “It’s really gorgeous.”

Ribbeck cares about spit because she’s trying to deconstruct how glycans, tiny sugar molecules hidden inside mucus, work to keep a particular organism healthy. Scientists already know that mucus is important in maintaining human health and supporting the microbiome. The glycans’ job, according to Ribbeck and others’ work, is critical. They specialize in managing microorganisms that can be beneficial—assisting in food digestion, regulating immunity, and protecting against germs—but that can be harmful if they outcompete one another or become virulent, potentially leading to infection. Like microscopic conductors, glycans ensure that each section of the microbial orchestra is playing in harmony.

In a study published this month in Nature Chemical Biology, Ribbeck and her collaborators showed how glycans keep a fungus called Candida albicans (C. albicans) from becoming problematic. The line between friend and foe is nebulously drawn in the case of C. albicans. The fungus is polymorphic, meaning it can take on different shapes: a rounded, yeast-like structure (generally considered normal) can turn into a filamented, thread-like shape associated with virulence. While the fungus can contribute to immunity, it can also lead to yeast infections or, even more seriously, a systemic infection of the bloodstream.

Sing Sing Way, a physician-scientist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center who was not involved in this study, has researched the ways that shapeshifting Candida can be beneficial for human health. “Complex microbes like Candida have co-evolved with not just humans, but other mammalian hosts, for a long, long time,” Way says. “They’ve developed strategies where it’s good for both.” He thinks that if we understand why and how the fungi change form, we can exploit this relationship to keep them on good behavior.

Ribbeck’s group had done previous work establishing how mucus stops other microbes from becoming dangerous. In this new set of experiments, the scientists wanted to know exactly how it works in the case of C. albicans.

But first, they needed a lot of goo. “It’s surprisingly hard to collect larger volumes of mucus,” Ribbeck says. “It’s a really precious material.” The team collected three kinds of mucus using different methods: aspirating human spit (similar to the way a dentist uses a suction tube to suck saliva from under a patient’s tongue), as well as scraping the insides of pig intestines and stomachs. Then, they incubated the purified mucus with C. albicans inside a well plate—a clear rectangular dish, punctuated with 96 beehive-like holes containing small volumes of fungi.

They discovered that all three types of mucus stopped the fungi from adhering to the plate, compared to a negative control. C. albicans also appeared rounder when the mucus was present, as opposed to the elongated version associated with filamentation. This, the researchers thought, indicated that the mucus could stop the fungus from sticking to bodily surfaces or forming biofilms, which are stringy, intertwined layers of the fungi that are associated with infections.