The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) has long been invisible to the naked eye but shrouded in mystery and controversy. Until recently, coups were seen as internal struggles and manifestations of a people who desired regime change, but many believe that they are often planned and legitimized from the outside and then projected as signs of local instability. They are not sudden, sharp actions, in fact, they are built on long-term processes to control political orders, financial networks, and natural resources. CIA covert operations are by their very nature hard to prove definitively, but research into the agency’s work, declassified documents, and revelations by former CIA employees have unwound a piece of complicated information.

Congo’s Patrice Lumumba’s death in 1961 was followed by that of the opposition leader of Cameroon, Felix Mounie, who was poisoned in 1960. Sylvanas Olympio, the leader of Togo, was killed in 1963. Mehdi Ben Barka, leader of the Moroccan opposition movement, was kidnapped in France in 1965, and his body was never found. Eduardo Mondlane, leader of Mozambique’s FELIMO, fighting for independence from the Portuguese, died from a parcel bomb in 1969, as did, of course, Ghana’s Kwame and Nkrumah.

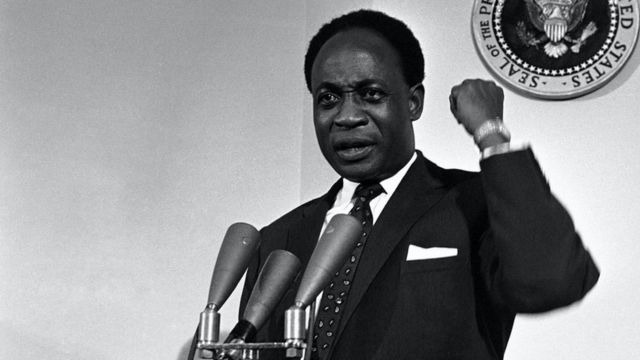

Kwame Nkrumah’s ideologies were rooted in his vision of the United States of Africa. He believed that the only way for Africa to truly progress was through the creation of a federal state based on a common market, a common currency, a unified army, and a common foreign policy that would enable Africa to solve internal conflicts as well as defend itself against external threats. Dr. Nkrumah believed that Ghana’s independence from Britain’s colonial rule in 1957 was not only significant for Ghana but also for the rest of the continent. Consistent with his independence day declaration that Ghana’s independence was meaningless unless it was linked with the total liberation of the entire continent. Nkrumah trained African Liberation Fighters, financed their movements, and encouraged them to send colonialists parking from their territories. Many say that as a result of Kwame Nkrumah’s support, as many as 35 African countries also attained their own independence within a decade after Ghana had achieved that fete.

According to some quotas, he became a threat and had to be taken out by any means necessary. According to many Nkrumahists, his efforts to unite Africa under one government and his anti-Imperialist stunts attracted the resentment of the West, particularly the United States. In his book, Dark Days in Ghana, Nkrumah alleged that the CIA and other intelligence agencies were actively plotting to undermine his government using bribes and premises of political power to recruit traitors in his government. Although his critics dismissed these claims as delusional, declassified documents later suggested that the CIA had orchestrated the plot to get rid of the man who, according to the files, did more to undermine American interests than any other black African.

They say that the U.S. government was determined to get rid of Nkrumah before he managed to unite Africa under one government. They worked with senior Ghanaian military and police officers supported by British and American diplomats and intelligence officers who provided long-term planning, financing, and logistical aid to mastermind Nkrumah’s overthrow. It is alleged that the UK and the U.S. began discussions of regime change in Ghana in 1961. Nkrumah’s overpowering desire to export his brand of nationalism unquestionably made Ghana one of the former practitioners of subversion in Africa. He resisted economic policies proposed by the International Monetary Fund and implemented by the World Bank. He was a patron of the Bureau of African Affairs, which allegedly had agents supporting nationalist and opposition movements across Africa, like the Ivory Coast, Upper Volta, now Burkina Faso, Niger, Togo, Senegal, Cameroon, Liberia, and Nigeria, with the ultimate goal of assisting more radical leaders to get to positions of power.

He even mounted an offensive against apartheid South Africa by providing money and training to the military wing of the African National Congress in the years leading to the coup. It is alleged that Washington withheld loans from Ghana and worked to lower world cocoa prices through stockpiling in order to deprive Nkrumah of much-needed foreign exchange.

U.S. ambassador, Franklin Williams, one of the first African Americans to be ambassador, presented his credentials to Nkrumah on January 17, 1966, a few weeks before the coup, but before taking up his position, it is alleged that he exchanged private correspondences with friends, bragging that he would soon be running the country. Three weeks before the coup, an editorial in the Spark, a newspaper founded by Nkrumah, asked why the U.S. would send an African-American ambassador to Ghana when they did not support racial equity in their own country and would surely not send a black ambassador to a European nation. There was speculation that Nkrumah saw his appointment as a sign of disrespect and felt that the U.S. was sending a black ambassador to do their dirty work.

On February 21st, 1966, three days before the coup, Nkrumah went on a state visit to Vietnam to negotiate a peaceful settlement to the U.S. war in Vietnam. The United States had encouraged him to go on the diplomatic mission and had indeed promised to halt the bombing of North Vietnam. During the same time, a group of 600 soldiers stationed in the northern part of Ghana was ordered to start moving south to Accra, a distance of about 445 miles or 700 kilometers. According to sources, they were told at first that they were mobilizing to respond to the situation in southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe. When they reached the capital, the coup leaders told the soldiers that Nkrumah was meeting with Vietnamese President, Ho Chi Minh, in preparation for the deployment of Ghanaian soldiers to the Vietnam War.

Later, the soldiers were told they were going to be deployed in southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, to fight against the white government of Ian Smith. It is alleged that the coup plotters riled up the soldiers and justified their takeover by charging that the Nkrumah administration was abusive and corrupt. They explained that they were disturbed by Kwame Nkrumah’s aggressive involvement in African politics and by his belief that Ghanaian troops could be sent anywhere in Africa to fight so-called liberation wars. The coup led to the capture of various key government institutions, the state broadcasting house, and the International Communication buildings were captured quickly. The heaviest fighting broke out at the Flagstaff House, which was the presidential residence. But when Colonel E.K. Kotoka threatened to bomb the presidential residence if resistance continued, Nkrumah’s wife, Fathia, advised the guards to surrender. The coup leaders informed the public of the regime change over the radio at dawn on February 24, 1966.

Many believe that even though senior officials of the Ghana Army carried out the coup on the ground, the U.S. intelligence agency pulled the strings and called the shots from behind the scenes. The coup statement over the radio was as follows, ‘Fellow citizens of Ghana, I have come to inform you that the military, in cooperation with the Ghana Police, has taken over the government of Ghana. Today, the myth surrounding Nkrumah has been broken. Parliament is dissolved. and Kwame Nkrumah is dismissed from office. All ministers have also been dismissed. The ruling Convention People’s Party is disbanded with effect from now. It will be illegal for any person to belong to it.’

It is believed that while in Vietnam, a 50-man entourage accompanying Dr. Nkrumah ended up deserting him when a CIA telegram informed Washington of the coup. According to the military, 20 members of the presidential guard had been killed and 25 wounded. Others suggest a death toll of 1600. After the coup, Dr. Kwame Nkrumah went into exile. He sought refuge from his close ally, Sekou Toure, the president of Guinea, who made him an honorary co-president of that country.

An ex-CIA whistleblower stationed in Africa, John Stockwell, made comments about the role of the CIA in Nkrumah’s overthrow. Part of his account said Howard Bain, who was the CIA station chief in Accra, engineered the overthrow of Kwame Nkrumah.

Many believe that one of the main reasons for Nkrumah’s overthrow was that he started soliciting support from the Soviet Union in the fight for African liberation.

While some say that Dr. Kwame Nkrumah was the architect of his own downfall because of the introduction of a one-party state in Ghana and his alignment with China and the Soviet Union, others say that he was just a threat that had to be taken off because of his one-Africa vision.

Content created and supplied by: EdwardLadzekpo (via Opera

News )

, . , . () , , , , , , , , . / , and/or . , , and/or , and/or