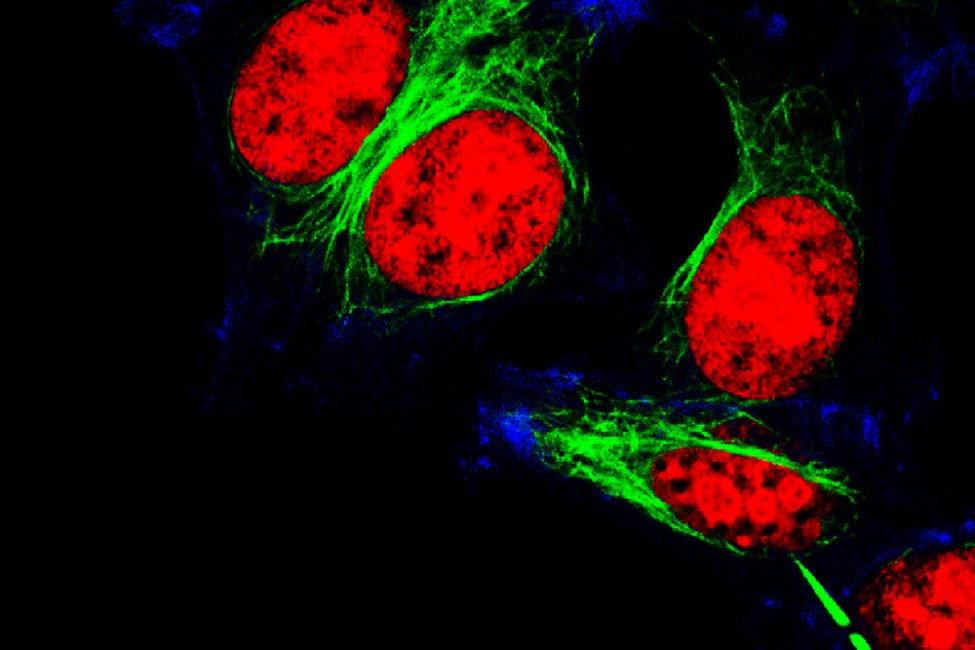

Researchers believe they have found how ovarian cancer develops in some women. File photo by Vshivkova/Shutterstock

Dec. 28 (UPI) — Researchers at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles believe they have learned how a genetic mutation places some women at high risk for ovarian cancer, according to an article published Tuesday by the journal Cell Reports.

Based on experiments in lab-created models of fallopian tube tissue grown from stem cells, women with a genetic mutation called BRCA-1 begin to develop the deadly form of cancer in the organ that connects the ovaries with the uterus, the researchers said.

In addition to showing how ovarian cancer is “seeded” in the fallopian tubes of women with BRCA-1 mutations, the approach used in the experiments could help predict which women will develop ovarian cancer, perhaps decades in advance, they said.

It could also be used to assess whether a drug might work against the disease, the researchers said.

“Our data supports recent research indicating that ovarian cancer [in women with BRCA-1 mutations] actually begins with cancerous lesions in the fallopian tube linings,” Clive Svendsen, one of the researchers, said in a press release.

“If we can detect these abnormalities at the outset, we may be able to short-circuit the ovarian cancer,” said Svendsen, executive director of the Cedars-Sinai Board of Governors Regenerative Medicine Institute.

Ovarian cancer is the largest cause of gynecologic cancer deaths in the United States, in part because symptoms are often undetected. It often goes undiagnosed until the tumors are in advanced stages and have spread past the ovaries, according to the American Cancer Society.

Although the lifetime risk for developing ovarian cancer is less than 2%, the estimated risk for women who carry a mutation in the so-called BRCA-1 gene is between 35% and 70%, the society estimates.

As a result, many women with BRCA-1 mutations choose to have their breasts or ovaries and fallopian tubes surgically removed, even though they may never develop cancers in these tissues, Svendsen and his colleagues said.

For this study, the research team generated induced pluripotent stem cells, which can produce any type of cell.

They used blood samples taken from young ovarian cancer patients who had the BRCA-1 mutation and a control group of healthy women.

The researchers then used the induced pluripotent stem cells to produce organoids, or small, simplified versions, of the lining of fallopian tubes for the two groups and compared them.

Each organoid carried the genes of the women who provided the blood sample, making it a “twin” of their actual fallopian tube linings, the researchers said.

“We were surprised to find multiple cellular pathologies consistent with cancer development only in the organoids from the BRCA-1 patients,” researcher Nur Yucer said in the press release.

“Organoids derived from women with the most aggressive ovarian cancer displayed the most severe organoid pathology,” said Yucer, a project scientist in Svendsen’s lab at Cedars-Sinai.

In addition to revealing the origins of ovarian cancer in women with the BRCA-1 mutation, the organoid technology could be used to determine if a drug might work against the disease, the researchers said.

The organoids can be used to test multiple drugs without exposing patients to them and their potential side effects, they said.

“This study [brings] us closer than ever to significantly improving the outcomes for women with this common type of ovarian cancer,” researcher Dr. Jeffrey Golden said in the press release.

“Building on these findings may one day allow us to provide early, lifesaving detection of ovarian cancer,” said Golden, vice dean of research and director of the Burns and Allen Research Institute at Cedars-Sinai.