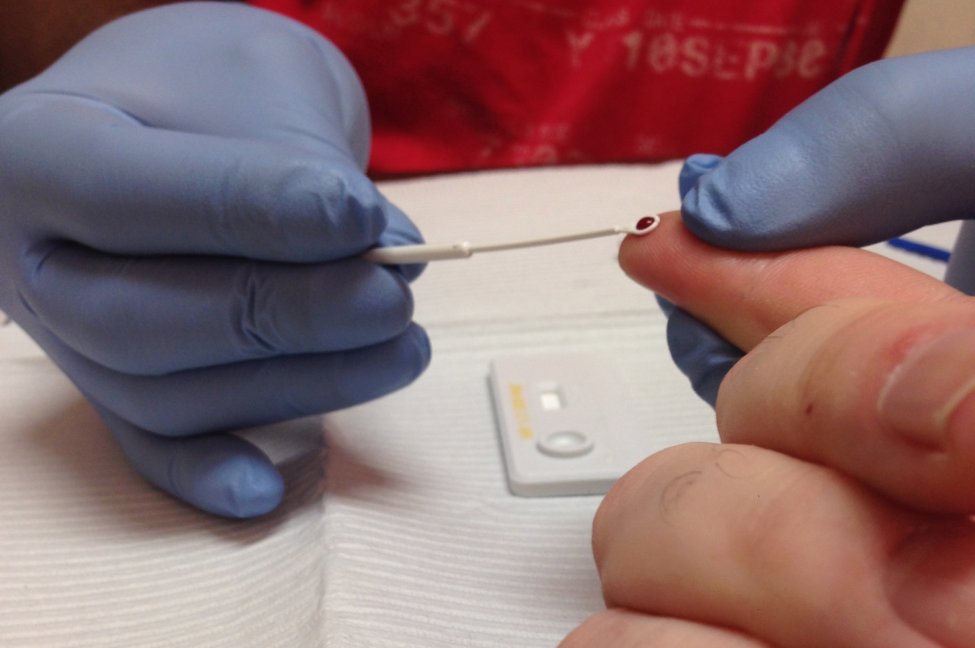

Gay and bisexual men of color in the United States have less access to diagnostic services, such as HIV Rapid Testing, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Photo by Equality Michigan/Wikimedia Commons

Nov. 30 (UPI) — New HIV infections have increased among Hispanic gay and bisexual men in the United States over the past decade, according to figures released Tuesday by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

At the same time, they have declined only slightly among Black gay and bisexual men, the data showed.

This is despite significant drops in new infections among White gay and bisexual men over the same period and federal initiatives designed to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

From 2010 to 2019, the most recent year with data available, the number of new HIV infections among Hispanic gay and bisexual men rose to 7,900 from 6,800.

Over the same period, new infections among Black gay and bisexual men fell to 8,900 in 2019 from 9,000 in 2010, the CDC said.

Meanwhile, new cases among White gay and bisexual men declined to 5,100 new cases in 2019 from 7,500 in 2010, according to the agency.

“We have much more work to do to end this epidemic,” CDC Director Dr. Rochelle P. Walensky said Tuesday on a conference call with reporters.

“We have the scientific tools to end the HIV epidemic [but] to achieve this end we must acknowledge that inequities in access to care continue to exist and are an injustice,” she said.

In April, Walensky declared racism a threat to public health in the United States. She said Tuesday that the “disparities” highlighted in the new report are an example of how “systemic racism” impacts the health of communities affected by it.

About 35,000 people in the United States are diagnosed with HIV each year, according to the Department of Health and Human Services.

Since 2015, the number of new infections nationally has declined by about 8%, figures suggest.

However, Black and Hispanic people in the United States “have higher rates of HIV in their communities, thus raising the risk of new infections with each sexual or injection drug use encounter,” the agency, which oversees the CDC, says.

Roughly two-thirds of new HIV infections in the United States occur in gay and bisexual men, Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, director of the CDC’s Division of HIV Prevention, said on the call.

The new CDC report, which was published ahead of World AIDS Day on Wednesday, indicates that gay and bisexual men of color nationally were less likely to receive an HIV diagnosis, effective treatment or have access to pre-exposure prophylaxis drugs — a preventive drug regimen referred to as PrEP — compared with White gay and bisexual men.

In 2019, an estimated 83% of Black and 80% of Hispanic gay and bisexual men with HIV had been diagnosed, compared with 90% of White gay and bisexual men, the data showed.

Similarly, an estimated 62% of Black and 67% of Hispanic gay and bisexual men with diagnosed HIV were virally suppressed, meaning their treatment effectively controlled the virus, compared with 74% of White gay and bisexual men.

In addition, 27% of Black and 31% of Hispanic men were using PrEP, a drug regimen designed to prevent HIV infection, compared with 42% of White men.

The PrEP use data was collected from gay and bisexual men in 23 cities, where more than half of all people with HIV in large urban areas in the United States reside.

“There is an unequal reach of HIV diagnosis and treatment” in communities of color, Daskalakis said.

“There is no simply way to address healthcare inequities,” he said.

HIV-related stigma, or negative attitudes and beliefs about people with HIV, may be contributing to these disparities, Daskalakis said.

On an assessment of HIV-related stigma, with 0 representing no participant-reported stigma and 100 being the highest level of participant-reported stigma, scores among Black and Hispanic gay and bisexual men were about 20% higher than those of White gay and bisexual men.

In 2019, the federal government launched the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. initiative, which is intended to provide treatment and education services to at-risk populations, with the goal of reducing new virus cases by 90% by 2030.

“We have been focused on the COVID-19 pandemic for almost two years, but work on other public health challenges continues, including efforts to end the HIV epidemic,” Walensky said Tuesday.

The CDC’s first report indicating that communities of color were disproportionately affected by the HIV epidemic was issued in 1986, she said.

“Those disparities continue today and are an injustice and we must close these gaps … to end the epidemic,” Walensky said.