Durban – For generations, visitors to the Durban Natural Science Museum have been drawn to one of its the most prized possessions – a more than 2000-year-old Egyptian Mummy that has enthralled young and old alike.

According to history, the mummy was bought by the Durban Museum sometime between 1889 and 1910 from a British army officer, Major William Joseph Myers.

Myers brought the mummy from Egypt when he came to South Africa at the end of the 19th century, having served in Egypt for five years.

It is believed that Myers, who built up “the finest 19th-century private collection of ancient Egyptian antiquities which he bequeathed to his old school, Britain’s famous Eton College”, according to the Egyptian Society of South Africa, stole and smuggled the artefacts out of Egypt.

The mummy in the Durban Natural Science Museum is said to be that of a minor priest named Peten-Amun (Ptn-’Imn), thought to have died aged about 60 years.

It is believed to be from Akhmim, Upper Egypt, and comes from the early Ptolemaic period, 300 BC.

Now, as Egypt and several other African countries push to have their stolen and looted artefacts returned – from mostly European museums – the Durban Natural Science Museum is offering to return the mummy under its care.

Eric Apelgren, the Head of Department International and Governance Relations at the eThekwini Municipality, said the city would opening negotiations with the Egyptian Government through the embassy in Pretoria, to explore if the mummy in the Durban Natural Sceince Museum should be returned.

He said that in addition to keeping good relations with Egypt and Durban’s sister city, Alexandria, recent changes to legislation regarding how museums keep mortal remains have necessitated them to re-look at the mummy that the city had under its care.

“Secondly, globally Egypt has started a process of collecting these mummies that were taken out the country and begun documenting them and keeping them in specialised facilities, both for the own historical record, and preservation of their culture, but also as part of the tourist, offering,” Apelgren said.

He said that negotiations were still at a very early stage with the Egyptian government.

“We want to explore, firstly if they want the mummy back and secondly, how would we share the responsibility of getting them back, and then also looking at the scientific and technical logistical approvals process of that process.

“It’s really at a very early stage. We were checking that the Egyptian government whether they want the mummy that is in Durban, because if you look at the history of the how the money came here, it was a soldier who literally stole it. We, being an African city and being part of the continent, this something we must look at,” he said.

Apelgren said the challenge will come if the mummy is returned on how the city will keep the next generation of children interested in Egyptology.

“How do we sustain interest and passion, and, and knowledge of that history for local children without having the display there? I’m not sure if we need the display to do that, I don’t know. You might have to find other ways of inspiring our kids, the next generation to understand respect our history on the continent and in particular the history of Egypt,” he said.

According to the Egyptian Society of South Africa, there are three recorded ancient Egyptian mummies in South Africa. One is preserved in the Albany Museum in Grahamstown another in the National Cultural History Museum in Pretoria. And the third in the Durban Natural Science Museum.

According to an article published by the Egyptian Society of South Africa in November 1984, the mummy in Durban was X-rayed, revealing that the top half of the mummy was almost complete though there were a few molars and pre-molar teeth missing.

A minor fracture of one rib was evident through this had healed during the man’s lifetime. The density of the bone in the lower vertebral column suggested some arthritis. A mystery surrounds several missing bones: femur and tibia (left leg), patellae (left and right legs), and feet (left and right). All these bones were replaced by false structures, possibly made of wood and linen stuffing, within the wrappings.

The X-rays show that the shoulders have been compressed by the linen wrapping. Rapid decomposition prior to embalming can explain the disordered state of some Ptolemaic mummies, which seem to have disintegrated partly before mummification. As a result, parts of bodies were lost.

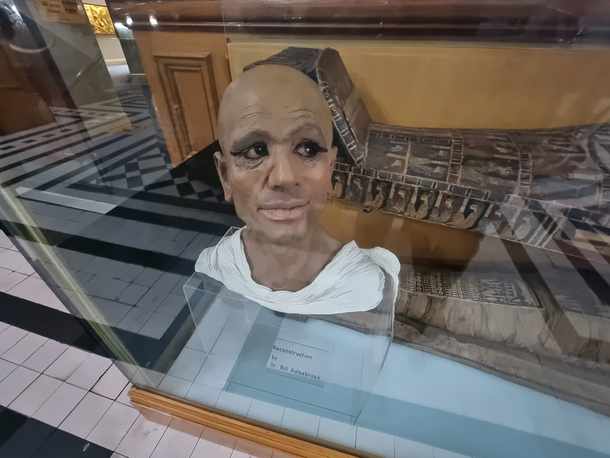

A reconstruction of the head of Peten-Amun was completed in 1990 by Dr Bill Aulsebrook who holds a PhD in Forensic Facial Reconstruction.

A Computerised Axial Tomography (CAT) scan was taken at the King Edward VIII Hospital in Durban and plastic templates were made from the individual sectional images. The templates were then assembled to form a three-dimensional construction of the skull. Using this reconstructed skull. Dr Aulsebrook was able to build up the facial musculature features. The bust is displayed alongside the coffin and mummy.

The mummified body is approximately 150 centimetres in length and the coffin itself about 175 centimetres long and 4 centimetres thick.

IOL

Credit IOL